Crossing the Rapido River – January 1944

Every generation of Texans carries with it a place of sacrifice that defines courage, loss, and memory. Just as the Alamo stands at the heart of Texas history, the name Rapido River holds a similar meaning for those who know the story of the 36th Infantry Division in Italy. Between 20 and 22 January 1944, along a narrow, flooded river south of Cassino, Texans faced one of the most punishing and tragic battles of the Italian Campaign — a battle remembered not for victory, but for the price paid.

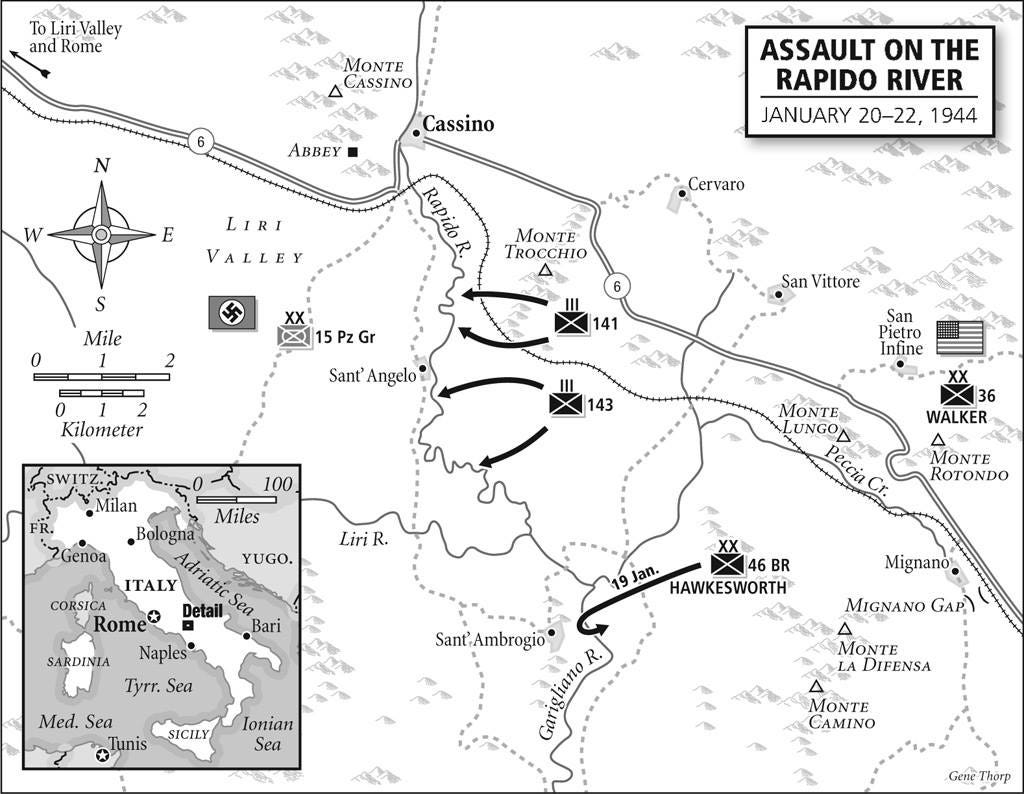

In January 1944 the Allied advance in Italy had stalled against the German Winter Line and the fortified Gustav Line. To break the deadlock and support the upcoming amphibious landing at Anzio, Allied command ordered renewed pressure along the front. The task of forcing a crossing of the river known locally as the Gari — and to many American soldiers as the Rapido — fell to the U.S. 36th Infantry Division, a Texas National Guard division commanded by Major General Fred L. Walker.

The mission was ambitious: cross the river under fire, establish a bridgehead, allow engineers to construct bridges, and open the gateway into the Liri Valley, the direct route to Rome. What the plan underestimated was not the courage of the men assigned to it, but the unforgiving logic of terrain and prepared defense.

German forces defending this sector — primarily elements of the 15th Panzergrenadier Division — occupied ideal defensive ground. The river flowed through a wide floodplain deliberately inundated by German engineers. The eastern approaches were flat, open, mined, and wired. Crossing sites were predictable and fully registered by German artillery. From the western bank and the surrounding rises, enemy observers could direct accurate fire onto every likely avenue of approach.

The assault force consisted mainly of the 141st Infantry Regiment on the northern axis and the 143rd Infantry Regiment on the southern axis. Both regiments committed multiple battalions in successive waves. The 142nd Infantry Regiment remained in division reserve. Artillery support was provided by divisional field artillery units, while the success of the operation depended critically on the engineers of the 111th Engineer Combat Battalion, tasked with clearing lanes, handling assault boats, and establishing bridges under fire.

The first assault began on the night of 20 January. Units moving toward the river were disrupted by mines, wire, flooding, and the difficulty of control in darkness and mud. Assault boats and bridging equipment had to be carried forward by hand across open ground already under artillery observation. German fire fell with devastating accuracy. Even so, fragments of companies reached the west bank and dug in among reeds and shallow embankments, isolated and exposed, waiting for the one factor that could transform sacrifice into success: bridging.

River crossings against prepared defenses are decided not at the water’s edge, but at the bridging sites. At the Rapido, engineers attempted to erect footbridges and then heavier bridges capable of supporting supplies, weapons, and armor. Each attempt failed. Temporary footbridges were destroyed by artillery or collapsed under damage and current. Heavier bridging efforts were broken apart before completion. Without protected bridges, infantry on the west bank could not be reinforced, resupplied, or supported. Once bridging failed, the fate of the assault was sealed.

A renewed effort on 21 January brought further losses but no change in conditions. In the northern sector, elements of the 141st Infantry Regiment were isolated and shattered. In the southern sector, the 143rd Infantry Regiment also suffered heavily but managed to withdraw more survivors. By 22 January, remaining west-bank elements were cut off. Many were killed; others were wounded or captured. Entire companies ceased to exist as fighting units.

In less than forty-eight hours, the 36th Infantry Division suffered more than 1,680 casualties — killed, wounded, missing, and captured. The losses fell most heavily on the 141st Infantry Regiment, where entire companies ceased to exist as effective fighting units after being isolated on the west bank. German casualties, by contrast, were relatively light — a reflection of terrain, preparation, and control of fire.

The Rapido River became a defining case of command friction. General Walker had warned before the assault that an infantry crossing without secured bridging risked disaster. His concerns were based on terrain and enemy preparedness, not on doubt about his men. At Fifth Army level, however, the crossing was viewed as necessary to maintain pressure along the Gustav Line and support the broader strategic plan tied to Anzio. The result was a battle that has been debated ever since — not because courage was lacking, but because tactical reality could not support strategic intent.

Seen through the lens of battlefield decision-making, several moments stand out. The selection of crossing sites offered minimal concealment and canalized movement into predictable lanes. Once small elements gained the west bank, commanders faced a brutal dilemma: reinforce a foothold that could not be sustained, or attempt withdrawal under fire. As bridging attempts failed, the commitment of additional infantry no longer increased the probability of success — only the scale of losses. These terrain-driven decision points explain why the battle remains debated: not because courage was absent, but because the conditions required for a successful river assault were never truly achieved.

Today, the Rapido flows quietly through farmland, its banks giving little hint of the violence witnessed in January 1944. Yet the ground itself still explains the battle with uncompromising clarity. For Texans, the Rapido deserves remembrance not as a footnote, but as a place of sacrifice — a place to be remembered with the same solemn respect reserved for the Alamo.

Explore the battlefield today:

→

Explore the 36th Infantry Division Battlefield Tour

Attachments (Primary Sources & Archives)

To preserve the Rapido operation in the words of those who planned it, fought it, and recorded it, the following contemporary documents and archival resources are essential reading. They illuminate the terrain problem, the engineering crisis, unit-level actions, casualty patterns, and the command environment that shaped the outcome.

-

Gen. Fred L. Walker – Comments on the Rapido (archival document, PDF)

Open PDF -

141st Infantry Regiment – After Action Report (to May 1944) (PDF)

Open PDF -

143rd Infantry Regiment – After Action Report (to September 1944) (PDF)

Open PDF

Medal of Honor – Thomas & McCall (36th Infantry Division)

Within the 36th Division’s combat record, Medal of Honor citations preserve intensely personal battlefield narratives — moments of leadership, sacrifice, and determination under fire. Even in a failed operation, courage did not fail.

For the complete citation texts and detailed narratives:

Open the Medal of Honor narratives (Texas Military Forces Museum)